A tale of two courtiers

24th June 2021

Local author Edward Glover compares the contrasting styles of two Renaissance diplomats – one whose notoriety resonates today and one whose legacy has faded – and asks what lessons both offer to present-day special advisers

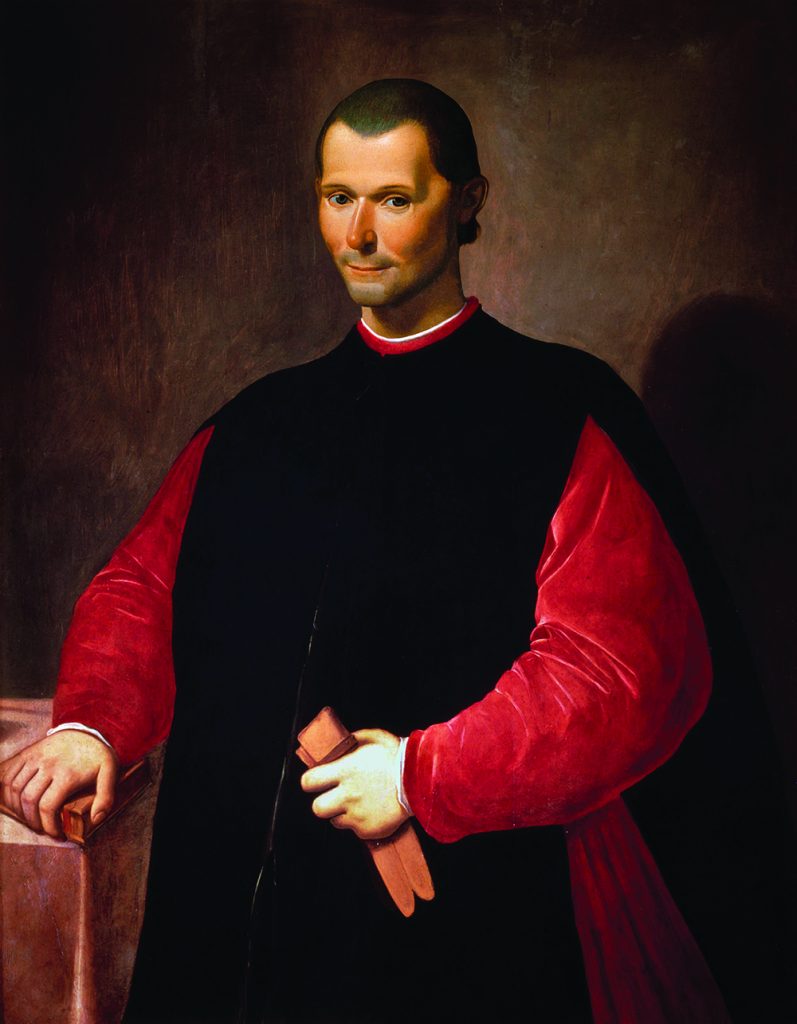

The name of Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527), diplomat and political theorist, is often linked with Renaissance power politics. His cold-blooded handbook – The Prince – advises how to outwit an opponent in the pursuit of glory and survival, how not to be shy of the use of immoral means to justify those two supreme ends. There are many quotes from his book but two are well-known.

“Never was anything great achieved without danger.“

“Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception.“

Fascination with the Florentine courtier has remained to the present day. In his book The New Machiavelli, published in 2011, about life inside Tony Blair’s No 10, Jonathan Powell attempts to show how the lessons Machiavelli derived from his experience as a court official still apply today – often reflected in political playbooks.

In the Italian Renaissance Machiavelli had a well-known contemporary. He was Baldassare Castiglione – born in 1478, nine years after Machiavelli’s birth, on his father’s estate at Casatico, in the territory of Mantua.

At the court of the Duke of Urbino – then regarded as one of the most brilliant in Italy – he was renowned as a scholar, intellectual, diplomat and author of The Book of the Courtier, first published in 1528, a year before his death. Lionised in his lifetime for erudition, literary skill and wisdom, after his death he was overshadowed.

Recalling his name from student days, I thought I would re-visit him – to find out who he was and what was his legacy?

In his lifetime, it was said he personified the gentlemanly virtues he extolled in his book. When the Emperor Charles V heard of Castiglione’s death he is said to have commented “I tell you one of the finest gentlemen in the world is dead.”

Raphael of Urbino’s portrait appears to confirm the Emperor’s judgement. In the words of Castiglione’s biographer Julia Cartwright over a 100 years ago:

“The noble brow and broad forehead, the fine eyes, with their clear, intense blue and vivid lightness, give the impression of intellectual power and refinement, tinged with a shade of habitual melancholy. All the spiritual charm and distinction of Castiglione’s nature, all the truth and loyalty of his character, are reflected in this incomparable work, which is a living example of the ideal gentleman and perfect courtier.”

The Man

His life and his book were regarded in the 16th century as highly representative of the Italian Renaissance. He grew up in noble surroundings and company, counting the Gonzaga princes of Mantua in his circle of friends. He studied at Milan University, learning Latin and Greek as well as jousting, fencing and wrestling. While at the Gonzaga court, he undertook numerous official and diplomatic missions on behalf of his master, the Marquess of Mantua.

At the beginning of the 16th century he moved to the city of Urbino. In 1504 he commanded a company of fifty men at arms in the service of Urbino’s ruler. In 1512, the Duke sent Castiglione to Rome as his ambassador. It’s there that he met Raphael the artist. In 1516 Castiglione married Ippolita Torelli, descendant of another noble Mantuan family. She died four years later while he was in Rome as the Duke of Mantua’s ambassador. In 1524 Pope Clement VII sent Castiglione to Spain as Apostolic Nuncio, where he became part of the court of the Emperor Charles V, who made him Bishop of Ávila. Castiglione died in 1529 in Toledo aged 50.

A monument was erected to him in Mantua. Its inscription referred to his many virtues and gifts and to his conduct of embassies to both England and Rome. I’ve so far been unable to find further information about the former.

The idea of writing The Courtier appears to have come to him in his earlier years with the Gonzaga family. It began to take shape during the years 1516-18, especially when he was in Rome representing the interests of his master and enjoying the company of old friends from Urbino, now papal officials. Though he showed the emerging manuscript to several of his friends, he did little to advance its publication.

Eventually, to forestall impending unauthorised publication by others, in 1527 he sent the manuscript to the Aldine Press in Venice. He specified to his steward that 1030 copies were to be published and that he intended to pay half the expenses so that 500 copies would be his. The edition was to be printed “on fine paper, as smooth and beautiful as possible – in fact the best that can be found in Venice”.

In a subsequent letter to Don Michel de Silva – a friend in Rome representing the Portuguese King – to whom the book was dedicated, Castiglione modestly disclaimed any pretensions to literary achievement, resigning himself to the judgement of time.

The Book

Though conversational in style, it’s a manual about how to be a successful courtier. He should be well-rounded, able to do many things – from playing a musical instrument, to reciting a sonnet, to competing in a sport. The ideal female courtier should be reserved, gracious and above all beautiful. All courtiers should be exponents of the art of making everything look easy.

Some scholars have argued that the contents do not necessarily display great originality of thought. Instead, it’s a replication of medieval ideas of chivalry, of classical virtues and expressions of contemporary humanist views to be found in northern Italy at that time. And it borrows extensively from Plato, Cicero and Livy.

Nor, unlike Machiavelli’s The Prince, do its expositions add much to the issues confronting Italy at that time – military weakness, the role of women in society, the best type of government, the standing of the fine arts; and the true nature of perfect love. That said, Castiglione did contribute to other lively topics – for example the need for a universal vernacular to overcome Italy’s several regional languages.

Others have argued that it’s possible to trace the influence of the book on the aesthetics of the later Renaissance, such as grace, decorum and nonchalance which the great 16th century painter and art historian Giorgio Vasari expounded in his Great Lives of Painters, Sculptors and Architects.

It’s also a political book, justifying the courtier’s place in society as rightful successor to the medieval knight – upholding the concepts of dignity, mannered elegance and respect for martial accomplishments and literature, all at the service of a prince.

The Courtier was published at a time when the world of ideas and institutions it idealised were, as far as Italy was concerned, beginning to change significantly. It is possible that Castiglione realised that shortly before his death.

The book also began to incur the displeasure of the Church. When his son, Camillo, was preparing a new edition in 1576, he was warned that corrections would have to be made. The result was an expurgated edition in which references to Fortune and jokes about priests were removed. Early in the 18th century the Inquisitors in Padua had to be consulted when another new edition was in preparation. According to Julia Cartwright, it was not until 1894 that a correct version of the work from the original manuscript was finally edited.

And beyond Italy?

It appears the book had an influence for some time after Castiglione’s death. The first translation by Sir Thomas Hoby appeared in England in 1561 at a time of interest in Italian life and literature. Queen Elizabeth knighted Hoby in 1566 and sent him to Paris as ambassador.

In 1570, Roger Ascham, Queen Elizabeth’s tutor and later secretary, recommended the book be read with diligence. In Elizabethan literature, Ben Johnson uses The Courtier for a scene in Every Man out of his Humours; and a poem by Gabriel Harvey bases its praise of Sir Philip Sydney on his affinities with Castiglione’s perfect courtier.

Some conclusions

The book is not an easy read. In the opinion of George Bull, the editor of the 1967 published version, it shocks because it is so opposed to the spirit of the modern age – with its emphasis on social distinction and outward forms of polite behaviour, masking artificiality, insincerity, snobbery and selfish individualism. Bull adds that it glosses over the crudeness of Court life and the harshness of the world outside. In today’s terms, it does indeed portray a picture of the privileged elite.

In contrast, Machiavelli’s The Prince – first published in 1532 – has remained compelling because it represents true, brutal 16th century Florence – the wars, the feuds, bribery, intimidation and even murder to achieve power. The measures and stratagems he advocated are as fascinating today as they were in his lifetime – how a prince should behave to gain control and hold the state together by whatever means in perilous times. The present day is replete with examples.

In contrast, what Castiglione describes is pretence. Nonetheless, his book explores topics which might conceivably even today spark a discussion in a TV studio or on the radio. Such subjects might include the evolution of human expression; what makes a joke funny; what men and women look for in each other; what constitutes good government; and the true nature of love.

Some Castiglione quotes

“Practice in everything a certain nonchalance that shall conceal design and show that what is done and said is done without effort and almost without thought.”

“Men demonstrate their courage far more often in little things than in great.”

“There are many who think that they are marvellous if they can simply resemble a great man in some one thing; and often they seize only on the defect he has.”

Author: Edward Glover, www.edwardglover.co.uk

This article originally appeared in Inside Out magazine – Character Publishing – www.characterpublishing.co.uk